Last week I attended an intensive workshop on how to build games using HTML5 canvas and JavaScript. Even though I am not so interested in creating video games per se, I learned a lot of tips and tricks that these guys use to make their games perform well on the web. Since I am not trained as a programmer, I took advantage of the opportunity and asked a lot of questions. The teachers were extremely generous and patient with me and at the end I believe I started to understand some key ideas about JavaScript as an object oriented language.

While I was trying to process all these technical ideas, all I could think about was that the kinds of narrative structures that are possible when creating animation with code are novel to me. I don’t mean that narratives that emerge from programming or mathematical concepts are new to mediums like animation, but the way I am used to structure an animated film differs from what is possible in a digital medium that I can program myself. I have been making films (both in actual film and digital formats) where one thing is defined from the beginning, there is a linear timeline and the smallest subdivision of time is a single frame. Life makes sense and all is sane in this micro worlds of 24 or 30 frames per second.

But when the linear timeline disappears and the subdivisions seem endless with nested functions and tons of coded operations running simultaneously on every single frame, things change. What not so long ago was considered radical in animation: “non-linear”, “open-ended”, even the poorly called “non-narrative” films are not radical anymore but essential to the coded mediums. This idea was explained by Manovich in “The Language of New Media” a while back, I’ve been familiar with database narrative literature and artworks due to the subject matter of my dissertation. Yet it is only until now that I am deeply invested in learning how to code, that I begin to understand how this ideas affect my own work.

The epiphany came when I was introduced to the idea of “prototypes” in JavaScript. In not so technical terms, these guys are tiny pieces of instructions that inherit some rules from an ancestor. In other words, sort of like the DNA that defines a particular object that is rendered on screen. This tiny piece of information can define an aspect of this object on the way it looks, behaves, reacts to its surroundings, or anything that the programmer wants. Right then I realized that I was thinking the narrative of my work with data in a limited way, not taking advantage of the potential of having things de-contructed in such miniscule parts and that the data I work with can permeate deep into the structure that defines the work. I am excited to explore this conceptual understanding in the images I am doing now.

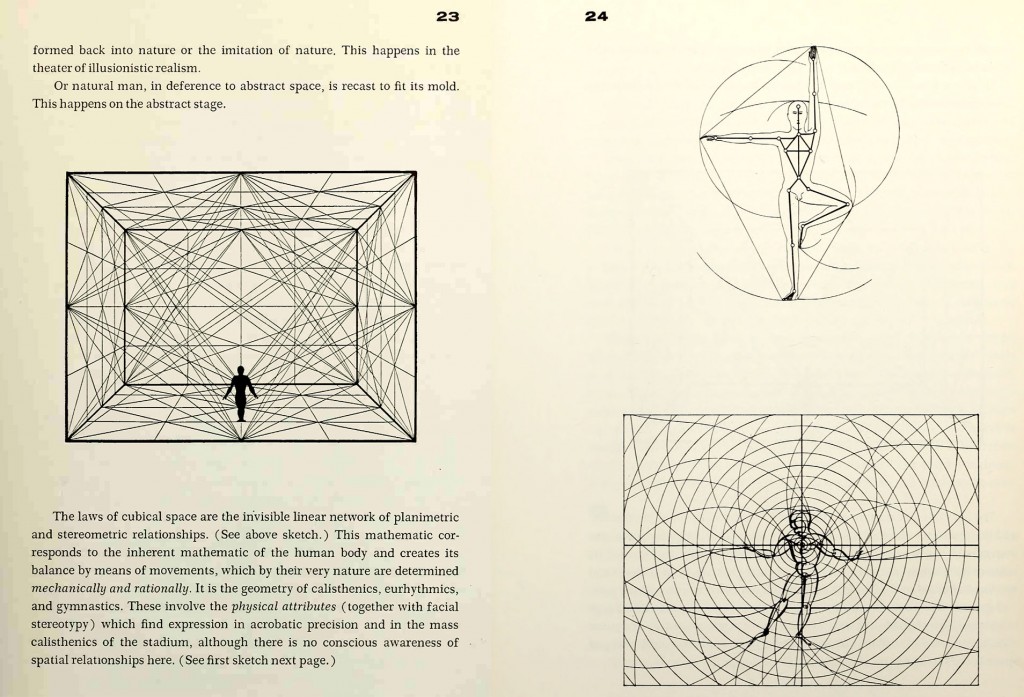

Images from Gropius Walter ed – “The Theater of the Bauhaus” (1996) p23-24.